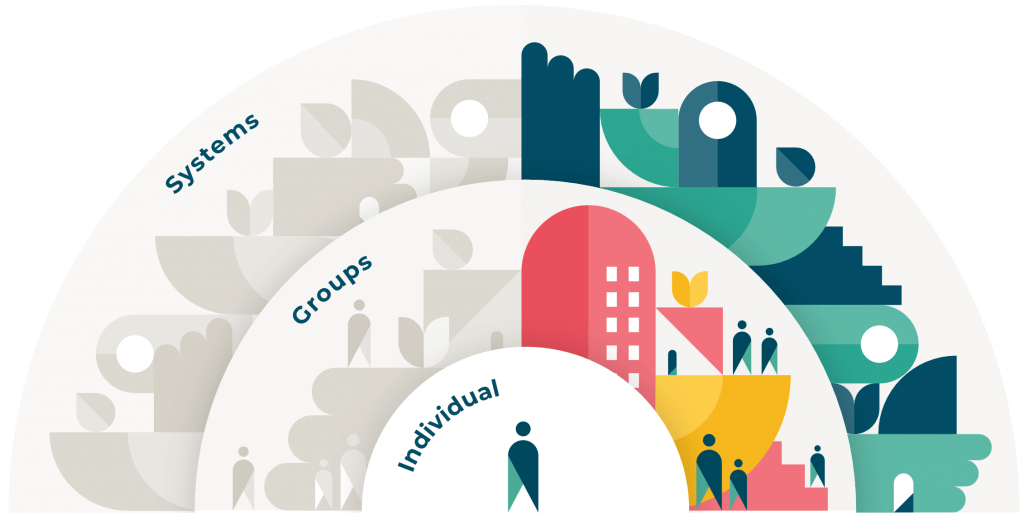

When approaching a new project, we’ve found that maintaining a simultaneous focus on individuals, groups (or teams) and systems helps us to be pragmatic about short term actions and realistic about long term change.

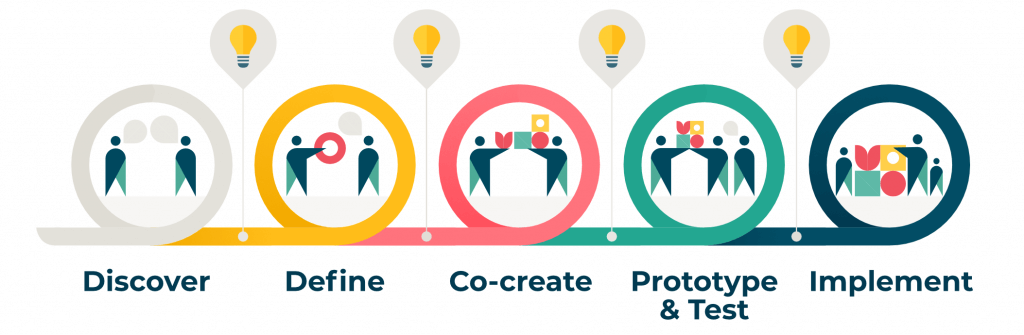

We weave our attention to these project levels throughout our process, which is heavily influenced by human-centered design, a collaborative problem-solving process that prioritizes input of people directly impacted by a design challenge. While every project is different, we generally follow five phases.

We know relationships are the most valuable vehicle for moving change initiatives forward. Our approach confronts even the stickiest problems with thoughtfulness, rigor, and an open mind – building lasting relationships along the way.

Our Process

|

Discover. A robust discovery phase sets the project context so we can understand the current state, desired future state, and possible ‘bridges’ to get there. |

|

Define. The problem definition phase helps ensure we are solving the right problem, as vetted thoroughly by those who may be experiencing it. |

|

Co-create, Prototype & Test, Implement. In the co-creation phase, we explore how we might solve the problem with key stakeholders, prototype and test potential solutions, and often assist with implementation. In our experience, the process we use is as important as the outcome – often the process is the product. |

Our Approach

|

Individuals. Our process always starts by talking to people. Understanding the motivations and behaviors of the individuals that ultimately shape a program or an organization helps us ensure key stakeholders truly are heard and included. |

|

Groups. These insights also begin to paint a picture of the group level. The picture that emerges of a group – be it a team, a department or an entire organization – provides important context about future possibilities. Based on what individuals have shared, what does that tell us about the group’s culture, current capacities and readiness for change? |

|

Systems. Finally, through desk research and further qualitative research, we develop an understanding of the systems within which the individuals are operating. Those systems could be partner networks, policy constraints or even market forces, each of which can set constraints on possible solutions, or offer opportunities for change. Systems thinking looks at problems holistically and investigates how the parts of a whole interrelate so that solutions do not exist in a vacuum, or unintentionally disrupt other parts of the system.Leveraging systems thinking helps us connect the dots between the people, processes and policies within human systems. |