Four Key Takeaways from a Co-Design Session in Humboldt County

Successes and lessons with social services providers and program participants

At a time when public benefits programs are in a state of uncertainty due to the utter chaos ensuing at the federal level, one rural community in Northern California came together for a half-day session to imagine creative ways to close “benefits cliffs” that make it hard for people to exit poverty.

According to Fed Communities, a collaboration among the 12 Reserve Banks of the Federal Reserve System, “a benefits cliff is the gap between what someone will be earning in a new job and the value of the public assistance benefits that person loses as a result.”

This means that for lower-income families, even the most marginal increase in pay can be met with the consequence of losing potentially thousands of dollars in public assistance benefits for their families, such as housing, healthcare, childcare and food.

The CivicMakers team, in collaboration with End Poverty in California (EPIC) and the McKinleyville Family Resource Center, are working to co-design a pilot program that closes benefits cliffs with community members and service providers in Humboldt County. The co-design session held on February 21st at The Center lays the groundwork for this program design.

While we work to synthesize and build on the insights of these conversations, we wanted to share key takeaways for designing and facilitating co-design sessions.

Tips for Leading Co-Design Sessions

1. Ensure your host site is a trusted community partner, at a location where both participants and program administrators feel comfortable engaging in creative work.

This effort has been blessed with a critical convener of public assistance in the region. The McKinleyville Family Resource Center offers an array of programs and services that “support, enrich, and sustain healthy community life.”

The Center – where we brought together stakeholders – is itself a co-location of nonprofits and government services. Among the services available on-site are a food pantry, an income program, community outreach and youth workforce development. Among our favorite features of The Center were the family-friendly bathrooms and onsite childcare, where tiny toilets reinforced a commitment to the space being for everyone who comes through the doors.

2. Make space for difficult conversations to emerge.

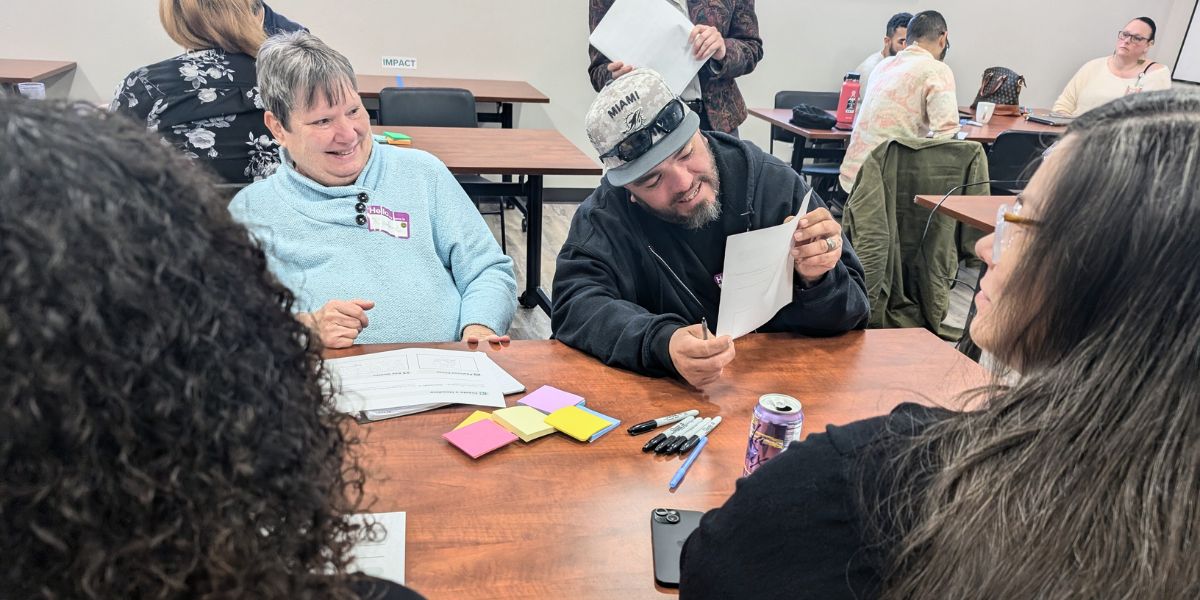

The co-design session included social service providers, from program and case managers to director-level staff, along with community members and staff at The Center.

Often, decision-makers don’t interact with program participants on a regular basis. As such, mixing up the participants into teams for the day that included a combination of community members/benefits recipients led to some difficult but important conversations to take place. One participant shared:

“Do I have to choose between having a dream or family? That’s my experience. Do I spend time with my kid or do I do my homework to graduate from a program to make money so I could leap over the benefits cliff?”

3. Put bigger idea generation at the beginning of the session, leave the afternoon for rest and reflection.

We started our session with a visioning exercise where we invited participants to write a news headline about how the program they were there to co-design impacted the community. While in teams, individuals were given quiet time to add quotes, sketch a cover photo and name the programs they’d like to design together. While certainly a feat in trying times, the exercise generated hope in the room, and individuals found common themes in each other’s visions.

At this stage of the design process, we are still shaping the structure of the program. A visioning exercise helps to bring the group together around shared goals and create a more tangible framework for them to brainstorm ideas. We invited the room to think about opportunities and priorities at different stages of the program: Start, Middle, End, Impact (or outcomes).

4. Manage your own expectations of what might happen in the session.

As facilitators, we meticulously design and refine engagements, prioritizing organic idea generation while having to manage the real constraints of time and energy in the room.

In this work, there is a palpable sense of hope and determination but an equal presence of direct and vicarious trauma from interacting with services that weren’t actually designed to lift families out of poverty. As facilitators, we must iterate on the fly to respond to emerging dynamics. Practice non-attachment to your own agenda.

Our team had to check our own assumptions about what might emerge as “prototypes” from the teams. Nearly every team used the materials provided to them (pipe cleaners, stickers, glue, googly eyes, etc.) to create physical representations of their ideas. Many of these were metaphors, such as a person with a parachute, representing a program element meant to give people a soft landing when they exit benefits programs.

Meanwhile, another team spent their prototype “building time” searching for a common experience they could build from. This meant more discussion than building. And that’s okay! It’s what needed to happen for that team and for this topic.

What’s Next?

The CivicMakers team is now knee deep in our data, and will be taking what we learned to create a menu of different pilot program options to share back with participants. All the ideas shared across different activities have given us plenty of building blocks to represent the diverse perspectives in the room.

We’re using these insights to direct analogous research to learn how other programs and communities are working to close benefits cliffs.

The ultimate goal is to design a compelling program that elevates and uplifts these lived experiences, centers dignity and autonomy, and is widely accessible. Stay tuned!