#CivicTech Primer: What is “civic tech”?

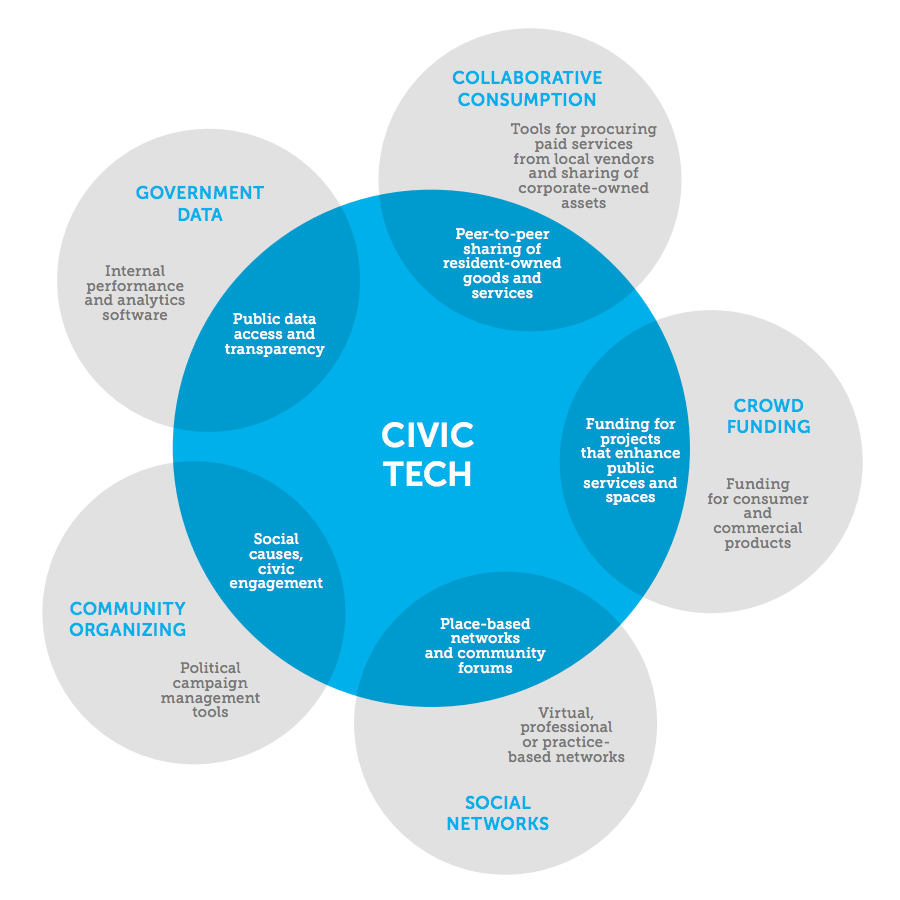

Image from the 2013 Knight Foundation report “The Emergence of Civic Tech”

Here in the Second Great Internet Bubble, we’ve come to accept Marc Andreessen’s maxim that “software is eating the world.” The evidence is outstanding for sectors like retail, social, finance and entertainment. And as you read this, software is quickly devouring many more sectors and systems, from transportation to health to energy. But our civic sphere — the relationships in the public world that gather us together into communities, cities, states and nations — stubbornly resists the advances of software.

Enter civic tech, a movement that aims to revitalize and transform some of our most fundamental societal institutions. A movement which also happens to account for $6.4 billion to be spent in 2015 to connect citizens to services, and to one another.

So What is “Civic Tech”?

For all the recent attention, civic tech remains an amorphous term. TechCrunch recently offered a narrow interpretation of civic tech as that used to “empower citizens or help make government more accessible, efficient and effective.” However, the Knight Foundation painted a broader picture in their 2013 report on the rise of civic tech, going beyond government to include “residents engaging in their communities, including sharing their time, information and resources.” Yet some draw a wider circle still. Beat reporter Alex Howard thinks of civic tech “as any tool or process that people as individuals or groups may use to affect the public arena.” And Micah Sifry of Personal Democracy Media adds that civic technology “cannot be neutral,” and only technology that is “used for public good and betters the lives of the many, not just the few” can be considered civic.

A brief history lesson may offer some clarity. Civic tech has its roots in government technology, a movement jump started by Tim O’Reilly’s formative Government 2.0 call to action in 2009. Decrying the “vending machine” model for government in which citizens put in our taxes and get services in return, he argued that we instead need an interoperable, extensible platform for government upon which anyone can build services that increase transparency, efficiency and participation.

Since that clarion call, a host of organizations like Code for America, a “Peace Corps for Geeks,” have carried the conversation forward, out of government and into the tech sector. Viable business models have developed, like that of Change.org and SeamlessDocs, and funders like Omidyar Network, Tumml, and GovTech Fund are starting to add civic tech to their portfolios. Tech inroads to government are being paved with the adoption of Chief Innovation Officers and open data portals at the local level and ground-breaking outfits like 18F and the U.S. Digital Service at the Federal. This maturation and expansion has led Tom Steinberg, founder of longstanding civic technology lab mySociety, to observe that, as a brand name, “civic tech” has won out over past alternatives like “eGovernment” and “Gov 2.0.”

Civic Tech is a Big Tent for Democracy

Which leads us to the present. I view civic tech as a new “big tent” movement for democracy that encapsulates many smaller segments, such as gov tech, online campaigning, digital advocacy, and voting tech. I am also a firm believer that “civic” is the operative word, meaning “us” and “we.” That is, people and communities, along with our hopes, dreams and needs, and the decisions that we make together to realize them. With software continually devouring so much of our lives, I see civic tech as an opportunity to embed “we” at the center of our technology. In civic tech, technology is always the means to an end, not the end itself.

As you can imagine, this perspective presents a civic tech space as wonderfully varied as the communities it aims to serve. Some will continue to be caught up on definitions. Is Facebook civic tech? What about SnapChat? Certainly, these tools can be used for both positive outcomes, like organizing a rally, or negative outcomes, like bullying or illegal surveillance. The dividing line comes back to intention. Was this technology designed to improve the public good and better the lives of the many?

Let’s take a look at some of my favorite civic tech tools to illustrate this criteria in action:

- Neighborland, a public input toolkit that “empowers civic leaders to collaborate with residents in an accessible, participatory, and enjoyable way.”

- Loomio, a collective decision-making service that helps groups discuss topics, build proposals and make decisions together.

- SeeClickFix, a communications platform for citizens to report and governments to manage non-emergency issues to foster “transparency, collaboration, and cooperation.

- Handup, a charitable giving platform that facilitates direct donations to homeless neighbors in need.

These and many other inspiring projects give me hope that the civic tech movement, and the passionate community behind it, will transform our communities, our workplaces and institutions to be more equitable, resilient, and even more fun. There are obstacles, of course. Some powerful people and institutions would rather not see communities empowered to make self-directed decisions. But I believe that the civic tech movement is putting people at the center of software development so that software doesn’t eat us, too. That’s why I founded CivicMakers, to highlight the growing array of civic tech solutions helping more people make better decisions together.

This is my first of four posts introducing civic tech to those new to the sector. I hope you follow along. And if you have a tool or project you’d like to share, or just want to know more about civic tech, I’d love to hear from you.