Community & Stakeholder Engagement

Co-Discovery: A Process for Impactful Projects

Synthesizing our findings at Code for San Francisco’s Civic Hack Night! From Left, Judi Brown (CivicMakers); Laura Ellena (Code for America); Susan Stuart Clark (Common Knowledge); Raelen & Raenelle Reed (Berkeley Reads)

At CivicMakers, we believe gathering the right mix of people, cultivating community and building trust are key ingredients for any successful public good project. Our approaches to problem-solving for the government agencies, nonprofits and social enterprises we work with put community engagement at the center. Diverse sets of perspectives reverberate out into problem definitions, methodologies and strategies to produce meaningful and relevant solutions for a wide range of humans.

We’re working to test and improve this approach and wanted to share our work, particularly with the field of civic tech and the civic hacking movement largely. Recently, we teamed up with Susan Stuart Clark of Common Knowledge Group to co-create a lightweight process that teams at Code for San Francisco could apply to their projects. Below is a brief overview of the process, followed by insights from our experience of “taking it to the streets” prior to Civic Hack Night.

Discover with, not for…

Civic technology’s mantra of “build with, not for” invites us to consider collaborating with the communities we aim to serve *before* anything is built or solutions offered. Enter Co-Discovery!

Co-Discovery is a process to help project teams generate relevant, game-changing problem statements by enhancing their capacity to listen and interact with real people experiencing real challenges. Co-Discovery contributes to an important evolution in civic innovation, which highlights new processes as much as new technologies, and building empathy into problem solving. The process allows project leaders, technologists and program specialists to help refine problem statement definitions by engaging directly with community members to develop solutions that are meaningful, relevant and evidence-based.

Here’s Susan’s perspective, based on her experience in the space:

“We are still seeing way too many projects from well meaning professionals who do not understand the context for the problem space they’re working on. Waiting until after you have defined the problem to seek out users’ perspectives means your project team may be playing on the wrong field moving toward the wrong goal.”

Defining the problem

Co-Discovery posits that a clearly defined problem statement is not possible without direct input from communities, individuals and institutions involved in the problem. Project teams are likely to have greater success defining the problem they hope to address by bringing those different perspectives to the table.

Like other aspects of a lean project, defining a problem statement benefits from an iterative approach. To start this iterative approach, consider the following questions: Is the problem something we can isolate to individuals, or does it require understanding a larger system? Is there an intermediary involved, such as a government agency or nonprofit? Who else is working on the problem? Then, initiate some “MVR for your MVP” — Minimum Viable Research for your Minimum Viable Product.

Levels of Co-Discovery

1. Programmatic

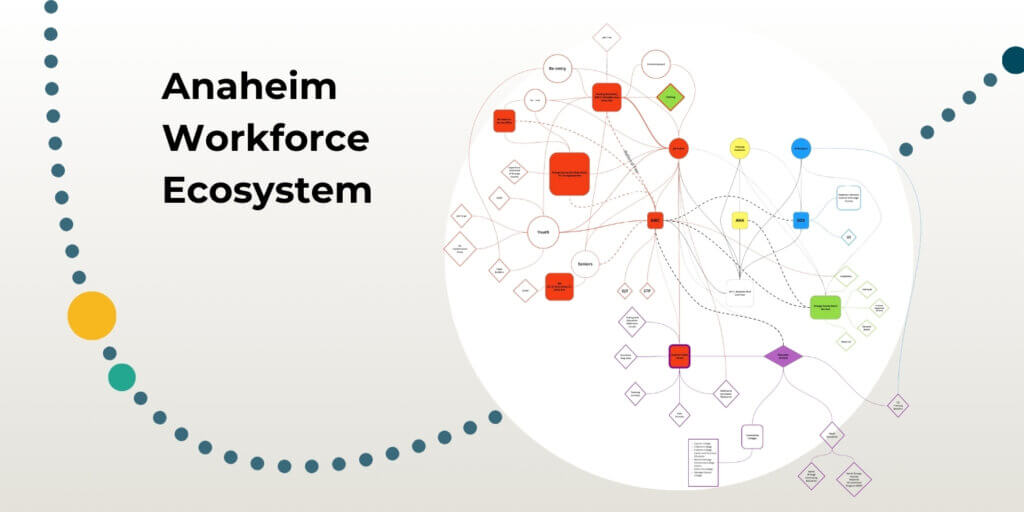

When conducting a landscape analysis of who is working on a particular problem, designing a simple survey or short interview guide for service providers is a great first step. This will help your team understand the types of players engaged in the issue, their audience(s) and primary pain points. Susan says: “A basic understanding of the ecosystem of the issue provides more solid ground for creating a promising project.”

2. Individual

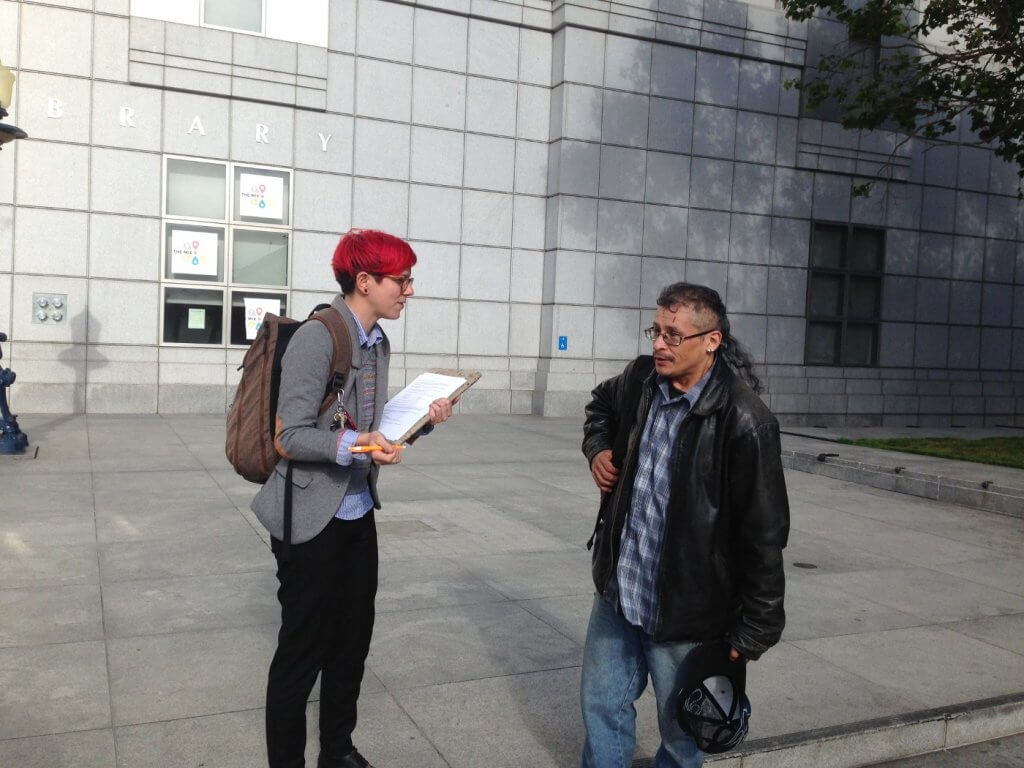

We’re inviting you to hit the streets! The other key element of discovery is to interact directly with end users. During this phase, which we affectionately call “Streetsearch,” your team talks to folks about the problem you’re working to solve, which they may be able to help you further define. This combines technology processes with the invaluable input of human insight.

Common Knowledge shared this example:

Direct insights from low income community members generated a high impact “get out the vote” program. The usual surveys indicated that people were not voting because it took too much time and they did not like politics. Partnering directly with nonvoters revealed a “performance anxiety” about the voting process (people thought it was going to be like taking a test at the DMV) as well as difficulties finding reliable nonpartisan information about the propositions in accessible language. The resulting Key to Community project for the California State Library doubled voting turnout among that audience.

Best Practices in Co-Discovery

As we continue to refine this process, we’re developing some best practices to share with all types of teams working on all types of public good projects. Here are some thoughts:

1. Remove assumptions!

This one seems pretty obvious but, in practice, removing assumptions about a particular problem and the communities experiencing the problem is not always easy. This practice involves acknowledging one’s own privileges and perspective, whether those include access to various levels of skill-building and education, or institutional advantages made possible through many layers of broken systems. It’s tough work, but the current state of political, cultural, and economic landscapes presents a HUGE opportunity for us to make meaningful improvements, together.

2. Immerse your team in context!

Put on your ethnographic lenses and jump into context. Spend some time with folks who look/act/think/feel/live differently than you. Step out of your comfort zone and engage with a constituency you’ve never engaged with previously. This helps to create mutual respect, empathy and broader understanding for individual and systemic interactions with a variety of problems, which will ultimately help you and your team to design impactful solutions.

3. Bring along “community ambassadors!”

Try to get in touch with some clients from service agencies you’ve identified working on a specific problem, and find an internal champion who will help you navigate the context. The need for cross-cultural translators when you’re doing your “streetsearch” can become apparent rather quickly, as folks who live within the particular context you’re exploring can help you create trust to get the valuable information needed to help shape your problem statement.

4. Subject matter expert(s)!

Lastly, we recommend having multiple subject matter experts, which can include program administrators as well as community members they serve. After all, who makes a better expert than an individual who has experienced a particular problem directly?

Interested?

Hello? Are you still there? Did we lose you? [Taps metaphorical microphone] is this thing on? Great! You’ve made it this far…congratulations! Join us at National Day of Civic Hacking which will feature workshops about how to use the community perspective in your work. And let us know if you want to connect with CivicMakers on a Co-Discovery process to fit your own unique context.

Special thanks to Susan Stuart Clark and Common Knowledge in the development of this story and process! ❤

Thanks to Lawrence Grodeska.